In the 1980s, the final quarter of the 20th century, Valeriy Koshlyakov began approaching the language of painting as though it were archaeological data. He posited that when the language of painting is missing, or at least not visible, in an artist’s work, this is a basis for concluding that the plane on which this work is located is empty, unclear and lacks illumination.

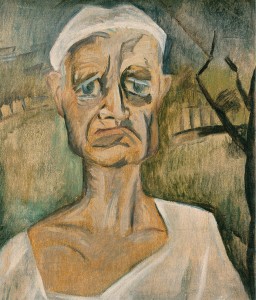

Mikhail Vrubel plunged into the very depths of art’s pitch-blackness in search of illumination. Larionov’s so-called “impressionistic” pieces of the 1900s contain much more inner light than external illumination, and this light became the central feature of his radiant works. Chekrygin wrote in his diary entry for January 25, 1921, “I always felt somewhat uncomfortable at the thought that a painting is merely nailed onto a lifeless canvas and that paints have no glow or transparency. I’d be overjoyed if a painting were displayed in a fog that covered everything, and an inner light shone from it … I would like to paint with rays of light, and upon completion, my spirit would devour them …” [17] This same light is noticeable in the works of Lev Zhegin, Yekaterina Belyakova, Peter Babichev, Wassily Koroteyev and Gregory Kostyukhin.

Light appears inside the painting – behind its text, underneath its surface, on the other side of outward appearance, at the exact point where the image disappears. Where does the image disappear? On Koroteyev’s unprimed and partially bare canvas, in the abortive, fragmented works of Koshlyakov, in the peeling paint of Schetinin’s works. It disappears when loss occurs, when something invisible or irreplaceable is discovered by stripping bare what is missing, lacking or unmanifested. This is the very beginning of the necessary and programmatic annihilation of all outward appearances.

It is obvious that outward appearances are not neutral. They come into being in order to rule the world. This is why the artist inquires: what makes the world such as it appears to be? What do I see? What changes in the world when I record its assertions?

The painting that an artist produces is simultaneousely the end and the new beginning of art.

The possibility of depicting the world objectively does not exist for the artist. As he examines everyday conventionality the artist discovers covert features that make the painting’s incompleteness and deficiency evident, even though critics may call the painting “objective”. Objectivity is the liberation of reality from the awareness of time. It is an outward appearance. It reflects contemporary culture’s cautious, non-present moment of action. The artist perceives the demand to be objective as a delusion, an invitation to sit at the bargaining table between the vendors and consumers of art. When society says that a system of objective evaluations exists, it is really saying that it does not want to be bothered by the intrusion of private meaning into communal culture’s ordered hierarchy of values.

The very contract that places limits on art is what allows contemporary culture to support this practice (agreeing to call it “art”) and present it as an element vital to society’s survival.