This viewpoint clarifies the ties that artists in the Brucke (“Bridge”) and Blauer Reiter (“Blue Rider”) artists’ societies had not only to their immediate predecessors – Vincent Van Gogh, Ferdinand Hodler, James Ensor, and Edvard Munch – but also to El Greco and the entire culture of mannerism. The works of an entire range of masters that appeared on the art scene during the war years (1914-1918) and early post-war years – Otto Dix, George Grosz, Max Beckmann, and others – gain a new level of appreciation when one takes into account the internal dialogue of these openly “social” and “critical” artists with not only the paintings and etchings of Francisco Goya, but also with the legacy of Peter Bruegel, Albrecht Durer, and the artists of the Danube school. The language of art is not limited to expressing social critique. The artist’s task is always much more complex and the role of the beholder more interesting.

During this overview of art history, one must keep in mind that what is meant is not certain formal parallels or analogies, but the particular and recognizable features of these works that place them as elements within a vast tradition. These are the units of meaning that testify to a specific art idiom, the elements that stand at the very foundation of each artist’s attitude towards art speech.

This is the case with Russian art as well. “Expressionism” here could be simply portrayed as an encroachment by a foreign culture and language, or an attempt to transplant European cultural features onto Russian soil. We could just limit “Russian expressionism” to those artists that represented Russia in the European art-scene. But both such approaches are dictated by a desire to place boundaries around the European cultural space, and have a place only in the European model of 20th century art history.

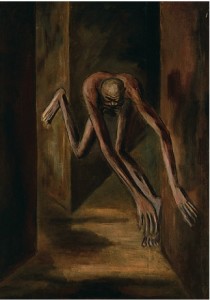

Such approaches ignore the pinnacles of 19th century Russian art – the works of Alexander Ivanov, Pavel Fedotov, and Nikolai Gay. These artists were all characterized by an internal, dynamic, increasingly open and visible quality of spiritualistic tension. This quality was communicated with the most expressive means: colour, technique, contour, and brush strokes. The tension constantly increased and reached its culmination in these artists’ later works. This was a movement towards uncovering the principle of spiritual origin or essence, known to contemporary culture as “spiritualism”. To accomplish this task required tremendous effort. It was not merely a fine gesture; it was a sheer act of will. It was so radical that it broke through the surface of their works, changed the world’s ordinary guises, and transformed people, the import of their everyday activities, and the meaning of books that have been reread many times.

In his “Reminiscences”, Nikolai Gay wrote, “Art has plunged into that which is incommensurably higher than itself.” [5]