Was it possible to implement such a separation and produce such a dependency? Could such a position of culture really be brought about? Or is such an interpretation of the Zeitgeist always fated or remain only a hope, a premonition, a mood – merely one of the utopian theses that the Russian intelligentsia is always working on?

Either way, the early 1920s was a time when humanism prevailed in art which strove to advance a feeling of freedom. At the same time, art took upon itself the function of building up life and fully believed that it had a special role in modern life regardless of the language it speaks.

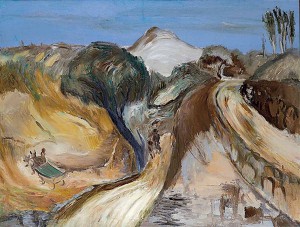

Of great importance was the fact that the majority of young progressive artists returned to grappling with the issues of painting proper. The appearance of the New Style of Painting contained in itself right from the very beginning the possibility of a break between the state and cutting-edge culture. Painting is non-narrative; it is a step away from political rhetorics. Painting is not obliged to show, describe or depict anything. It manifests itself as a continually developing language which is much larger than the boundaries of any political system. It is a universe in itself, reality par excellence, though it strives to speak the language of a contemporary man. A. Drevin, L. Zhegin, A. Labas, R. Falk, V. Koroteyev, B. Chernyshov, and Ye. Belyakova did not attempt to create a picture of the world; rather, they translated some of the characteristics and states of the world into the language of art and imbued it with the ability and possibility of speaking the language of modernity. It is not by chance that their paintings return to the elemental principles of creation, to the basics of form, rhythm, material and colour. These artists’ narrative deals with the appearing of a new world.

This type of painting does not endorse any political programmes and does not describe any social environment. Painting creates itself by recording the attempt of the language of culture to become a form — to become itself, to see, know and understand itself This is metaphysics; that is, a return to the eternal origin and sources of culture.

Many people who lived from 1918 to 1925 considered this period to be a time of turning away from abstract art in the realms of design and architecture, and building on the basis of that art a new style of figurative easel painting. I.e., this was a time of giving birth to a new language of “figurativity” on the basis of the avant-garde’s attainments. But in this, the emphasis was not on the word “painting,” but rather on “figurativity.” What was behind this? Was it a sense of responsibility before the state? Or the internal logic of the artistic process, which led contemporary art to engage in open dialogue with the legacy of previous centuries in its search for new humanistic and cultural meanings?