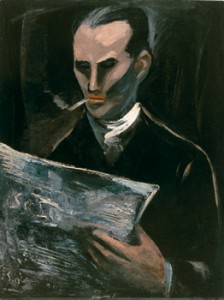

Rostislav Barto was another member of the Painters Guild. In the twenties, his name was well known to art critics and historians. Brilliant at drawing, Barto, who had his works shown at international exhibitions in Europe, America, and Japan, knew how to play with people’s imagination by citing various artistic languages. His work combined the methods of Millet, Corot and his favorite Derain (of whom “Man Reading a Magazine” is reminiscent) with the primitivism of Pirosmani and Oriental painting.

But attention on the part of critics does not always mean praise and an artist’s fame is not necessarily evidence of favorable change. In 1933, a book came out that, for many years to come, became the platform for attacks on the so-called “leftist” art, that is the art of those who were neither creating multiple images of the Soviet regime nor belonged to the bureaucratic elite of the Artists Union, set up in 1932. The book, written by Osip Beskin and published by Vsekokhudozhnik, was entitled Formalism in Art. Page 40 said: “Barto demonstrates by his work that he lives not just on the fringes of our society but outside it, as it were. He has created a world of his own or, more precisely, he has dragged an alien world into our society and wants to undermine the latter via that lifeless world of strange things and people who have been turned into things. Fortunately, today we can see these words as nothing but a high assessment of the work of that fine artist.

Portraits by Leonid Zusman make up a vivid gallery of grotesque images. The heroes of his paintings are fully authentic, sometimes ludicrous, ad often tragic. In his portraits one can see some purely personal, nearly intimate side to relationships between people.

Zusman was a very sincere artist. He empathized with all he was talking about. To be more exact, his work records his deep personal insight into his world, the city he lived in, whether it was Leningrad or Moscow, and people who were part of his life. People he portrayed were not invented. He might have been ironic about them, but he was just as ironic about his own life.

His paintings are utterly emotional, but simultaneously there is a lot of game-playing about them.

Leonid Zusman only talked about what he himself knew and felt. He could see that the world was in a permanent state of change. Such change was quite painful at times, but what did that matter if one thought of tiny human lives being thrown into a huge universal melting pot? An artist may be aware of this, but just imagine what talent he needs to be able to put it into his works. He could only be open for a change, accepting it whatever it was. This explains the sense of confusion, indecision or frustration characteristic for the people in his paintings – all this will go on for an indefinite time to come. He was aware that everyone had such feelings. This doesn’t add optimism to his paintings but gives them a different, very large, scale.