Russia adopted the official line that expressionism was a phenomenon spawned by a foreign cultural space, and thus had other historical, political and national boundaries. This is why in the second quarter of the 20th century expressionism left the stage of the official Soviet history of art, shunned dialogue with the establishment and was relegated to the private histories of various artists.

The artist refuses to be merely a functional cog in the modern machine of producing art and exchanging ideas within the artistic community. His future does not depend on the state of dialogue between ideology’s demand and artistic supply. His past does not depend on political commitments. His present is not determined by the desire to be contemporary.

If political culture considers the present its personal property and even identifies itself with modernity art, however, displays an inner drive to remove itself from modernity and offer an alternate present.

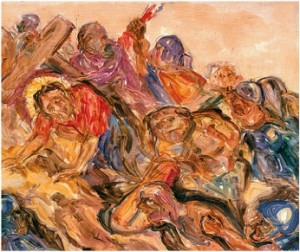

All ties to the past, all meanings, all streams of information are but the expressed thought of the artist. What becomes art is everything that happens to his body, his memory, his speech. It is those states of being in which “ego” comes into being and then ceases to exist. The artist is but a subjective measure for how close art has come to its own limitations. True artisthood is an unstable state of being; it can distinguish an artist’s entire career or be limited to only a single inspired work that he creates. The history of art is a constant return of different languages to the intention that draws them near to another but reveals their differences, irregardless of progress, the intention to say that which has not yet been said with words, or to bring to light the presence of the most esoteric, obscure meanings. Within this history, we see that Alexander Ivanov’s idiom of classicism turns to an anxious, flickering rhythm in his depictions of biblical themes; the psychologically tense genre art of Pavel Fedotov breaks loose into agitation in his later drawings and sketches; the academic realism of Nikolai Gay reproduces the collapse and dispersion of art language in a cultural space that finds conventionality and compromise unacceptable, a space where every attempt to tell about oneself turns into a phantasmagoria and where every word becomes a scream. We see that Mikhail Vrubel’s symbolism greatly exceeds the demands of the style as he strives to reveal the idiom of art as the language of Mystery, the birth of light out of the empty darkness of night, a night that in the end consumed the artist himself. This is why Alexander Blok wrote about Vrubel in the spring of 1910, “The artist lost his mind and drowned, first in the night of art, then in the night of death.” [14]

In the wake of Nietzsche, who recognized the contemporary state of thought as the end and final exhaustion of European metaphysics, the artist of the 20th century saw the exhaustion of art, and out of this emptiness asked, “What is in the process of becoming art?” This question had to do not with form, but with the meaning of art’s manifestation in the man of the new era.

The artist sees that nothing occurs apart from his will. At the same time, he realizes that he must remain open to the languages of art, which is both the obscure present and the force that pushes man to come into being.

The artist comes into being when he hears the presence of art as a question. It is his responsibility to provide an answer, to make a contract with the work of art. The languages itself compels him to speak and paint thus. All of his efforts are prescribed by features of this idiom, and his work is but the shadow of the idiom’s own work. Each piece of art proclaims the limitlessness of this language, but this limitlessness is realized only through the extreme subjectivity of the artist and has no independent value.

This inherent contradiction is confirmed and resolved by every artistic endeavor. Each intention and action of the artist becomes a denial of self, of personal experience and what is more, of salvation. The myth of Orpheus becomes the central myth of all time. As Blok wrote, “Art is Hades, monstrous and magnificent. Out of the gloom of this Hades the artist leads forth his images.” [15]